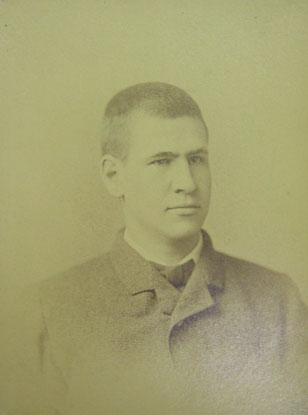

William Louis Abbott

(1860-1936)

William Louis Abbott

Academy Archives, Coll. 457, 4490

What if William Louis Abbott had listened to his father and become a doctor? America would have lost one of its greatest field naturalists, the discoverer of around 40 new species who collected more than 16,000 specimens of birds, mammals, and reptiles—not to mention anthropological artifacts, photographs, and handicrafts—from far-flung corners of the world. Although Abbott is remembered largely for his contributions to the Smithsonian, the Academy of Natural Sciences is home to his first collections, and is the institution that likely sparked his love for natural history. He remained a member of the Academy until the end of his life.

Possibly giving in to pressure from his father Redman Abbott, a wealthy Philadelphia silk merchant, William Abbott attended the University of Pennsylvania, earning a bachelor’s (1881) and a medical degree (1884) before pursuing post-graduate surgical studies in London—although his sister recalled that he never practiced medicine, except to treat minor ailments among his servants.

During summer vacations, Abbott pursued his real vocation: natural history. In 1880, he collected birds in Iowa and North Dakota. In 1883, the summer before his final year of medical school, Abbott collected assiduously in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. During his spare time as a student at Penn, he also prepared a collection of birds of Philadelphia and southern New Jersey.

Abbott generously gave the Academy his North American and Caribbean specimens, numbering nearly 3,000 birds. Throughout his life, Abbott continued to support the Academy, donating funds to help purchase the important A. Blayney Percival collection of East African birds and to support Harold H. King’s collection of birds in Sudan. His beloved sister Gertrude also donated funds for expeditions.

Great Horned Owl

(Bubo virginianus occidentalis)

ANSP 26435, Type

Passenger Pigeon

(Ecopistes migratorius)

ANSP 26334

Hispaniolan Emerald

(Chlorostilbon swainsonii)

ANSP 25161

Cuban Green Woodpecker

(Xiphidiopicus percussus)

ANSP 25199

Cuban Trogan

(Prioteius temnurus)

ANSP 25164

Yellow-breasted Barbet

(Trachyphonus margaritatus berberensis)

ANSP 104268

There are over 1,000 North American and Caribbean specimens in our W. L. Abbott collection. Many of the skins from the United States represent some of the very earliest specimen records from many parts of the Midwest. Several recent works on the birds of Iowa (where Abbott was accompanied by Joseph Krider, son of the notable Philadelphia collector and taxidermist John Krider) and South Dakota have cited these early Abbott study skins as the first records of many species for the respective states. A type specimen from Iowa in 1880 of the Great-horned Owl (Bubo virginianus occidentalis, ANSP 26435, Auk 13, p. 155) is among these early important specimens. Other important study skins from this collection are specimens of the now extinct Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) including two from Haddonfield, New Jersey (193830, 26334), collected between 1877 and 1879. The Caribbean birds from Abbott were collected on Hispaniola and Cuba in 1883. Virtually all of the endemic bird species, and many other taxa, from these two islands were collected during this trip. A few of the outstanding endemics include Oriente Warbler, Teretistris fornsi (25020-1), Cuban Trogan, Priotelus temnurus (25163-25166), and Cuban Green Woodpecker, Xiphidiopicus percussus (25198-9) from Cuba; and Palmchat, Dulus dominicus (25198-9), White-necked Crow, Corvus leucognaphalus (25111-7), and Hispaniolan Emerald, Chlorostilbon swainsonii (25161) from Hispaniola.

After receiving his inheritance in 1886, Abbott set out for Kilimanjaro to collect birds for the Smithsonian. For the better part of his life, Abbott kept moving. Zanzibar. Madagascar. The Seychelles. Kashmir. Himalayas. Turkistan. Pakistan. Bengal. Ceylon. In 1899, he designed and outfitted a boat, the Terrapin, and spent a decade exploring the islands around Southeast Asia with zoologist Cecil Boden Kloss and a crew of Malay sailors. Their collection of birds, small mammals, reptiles, and artifacts from the islands comprises the first extensive scientific survey of the region. In 1905, in recognition of his work, Abbott was made an honorary associate in zoology at the U.S. National Museum, as the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History was known then.

In 1909, Abbott reluctantly sold the Terrapin when a bacterial infection left him nearly blind. After treatment in Germany, he returned to the field, trapping in Kashmir because he could no longer shoot accurately. His zest for exploration was irrepressible. Even a near-fatal bout with dysentery in 1918 only put a temporary pause in his activities. Five years later, he discovered a living plagiodonta, a small rodent known only from fossils and until then thought to be extinct, in the Dominican Republic.

Abbott’s passion for fieldwork was part of his deeper Romantic sensibility, one that induced him to take up arms to fight for freedom in the manner of Lord Byron or T.E. Lawrence. In 1894, he journeyed from the Central Asian steppes to Madagascar to fight the French occupation alongside the Malagasy natives who snubbed him, preferring to lead their own liberation movement. He also fought for Cuban independence in the 1898 Spanish-American War. Approaching sixty years old and nearly blind, he volunteered as a doctor for the Allies in World War I. His offer was gently turned down.

When Abbott died in 1936 at his home on the eastern shore of Maryland, he left $100,000—one-fifth of his estate, the equivalent of nearly $1.6 million in today’s money—as well as his library, to the Smithsonian. But he left no memoir, scoffing that he would leave that to “some of these week-end explorers to do.” His specimens, then, must tell his story for him, and chart the map of his scientific adventures across the face of the globe.