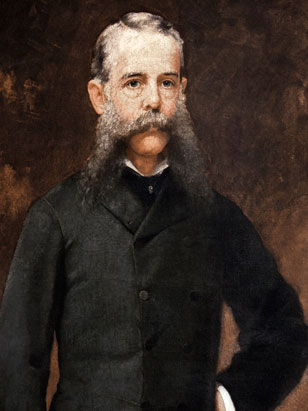

Clarence Howard Clark (1833-1906)

Clarence Howard Clark

Image courtesy of Clarence H. Clark

Clarence Howard Clark is probably best known to Philadelphians as the man behind Clark Park, a nine-acre green gem along Baltimore Avenue in the western part of the city. Clark, a prominent financier and developer who made a fortune consolidating railroads in the 1880s, used his substantial wealth and influence for public benefit as a patron of the arts and advocate for urban reform. His support of the Academy, including a gift to help fund the purchase of specimens from E.A. McIllhenny’s important 1897–1898 expedition to Alaska, complemented his other philanthropic activities, which aimed to enhance, beautify, and improve the city and the lives of its residents.

Little is recorded about Clark’s personal life prior to May 1873, when the Philadelphia Inquirer informed readers that the forty-year-old banker had returned from an “extensive tour” of Europe and Africa with his health “restored.” The illness or crisis that sent Clark abroad is undisclosed, but his arrival back in the city of his birth marked a turning point in his life. The following month, he resigned as president of the First National Bank and the National Life Insurance Company in order to focus on his role as a partner at E.W. Clark & Co., his father’s banking firm, as well as his executive position at Fidelity Trust. In November, he married his second wife, Marie Motley Davis, and intensified his involvement in Philadelphia’s social and civic life. In the following decade, Clark would lead investors through a series of purchases of railroads up and down the Eastern seaboard that increased the wealth of his shareholders as well as his own prestige. According to his obituary in the New York Times, he signed the first national banknote issued under the provisions of the National Banking Act of 1881.

The Academy of Natural Sciences was one of the first city institutions Clark became formally involved with; he was elected a member in 1867. Although he does not appear to have had a personal interest in natural history or ornithology, he strongly believed in the importance of bringing nature into the city. His funding of the purchase of the McIllhenny collection had significant impact on ornithological research.

Black Guillemot

(Cepphus grylle mandtii)

ANSP 37621

Ross’s Gull

(Rhodostethia rosea)

ANSP 37714

Spectacled Eider

(Somateria fischeri)

ANSP 37764

The McIllhenny collection is a classic example of how the importance of a collection can increase over time. At the time of its collection and purchase, the collection formed a spectacular series of arctic sea and water birds, including some particularly wonderful series of Cepphus grylle (Black Guillemot, ANSP 37615-37624), Rhodostethia rosea (Ross’s Gull, 37712-37714) and Somateria fischeri (Spectacled Eider, 37758-37769). As it happens, this collection was the first and remains the largest (both in numbers—at least 328 specimens—and species diversity) ever collected from this region of the world. These specimens are used regularly today to track environmental changes in the arctic region. The New York Times Magazine (Jan. 6, 2002) did a cover article on such research (based largely on samplings from this collection) by George Divoky and was so popular, Divoky was even invited to appear on the David Letterman show (Feb. 7, 2002). An additional specimen of note is 37604 which was originally described as a type, named after McIllhenny, of Long-eared Owl (Proc. ANSP, 1899, 51, p. 478) but has since been recognized as a synonym of another subspecies.

Clark was no passive philanthropist but actively engaged in finding solutions to a vexing question: how could modern, scientifically minded city planners and civic leaders make Philadelphia a more healthful, more beautiful (these two values were intimately connected) place for its citizens, especially children and the poor? Clark attended meetings of the Professional Social Science Association and was an executive committee member of the Open Space Association, which supported increased parkland and leisure grounds for city dwellers. When he granted land from his own private estate to create the public Clark Park in 1894, he was making good on his belief that increased exposure to nature improved the morals and health of urban residents, and helped alleviate the misery of poverty. His West Philadelphia residence was renowned for the beauty of its gardens that won prizes from the Horticultural Society where he was a benefactor.

An art-lover who assembled a notable private collection, Clark was one of the leading figures behind the University of the Arts, sponsoring American artists at a time when many wealthy Yankees sought their culture abroad. He was a founding member of the Union League established in 1862. Clark was also involved with the Zoological Society, the Free Library Association, the Academy of Music, Fairmount Park Art Association, and the University of Pennsylvania Archaeological Department, where he endowed a chair with his brother, Edward White Clark. Edward Clark’s son, Joseph Sill Clark, would distinguish himself as a Mayor of Philadelphia (1952-1956) and U.S. Senator (1957-1969).

Clarence H. Clark’s son from his first marriage, C. Howard Clark, followed in his father’s footsteps as a banker and community figure, supporting the Pennsylvania Historical Society and the College of Physicians, as well as being a member of the Art Club.

Although more research is needed to further illuminate Clarence H. Clark’s involvement with the Academy, it is clear that the institution shared many of his values: the advancement of scientific knowledge and the cultivation of wider appreciation for the beauty and wonder of the natural world.